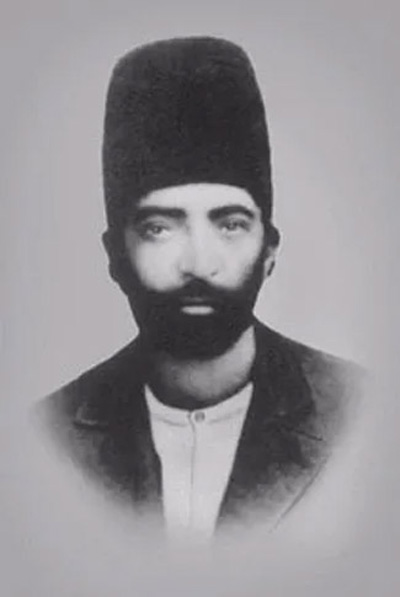

About Abbasali Gomrokchi

Abbas-Ali Khan was a prominent figure during his time, known for his close associations with the court of Nasser al-Din Shah Qajar. He held a high-ranking position as the director general of Customs (Gomrok) and was respected for his religious devotion, charitable nature, and well-mannered demeanor. Described as a generous and humorous individual, Abbas-Ali Khan’s character left a lasting impression on those who knew him.

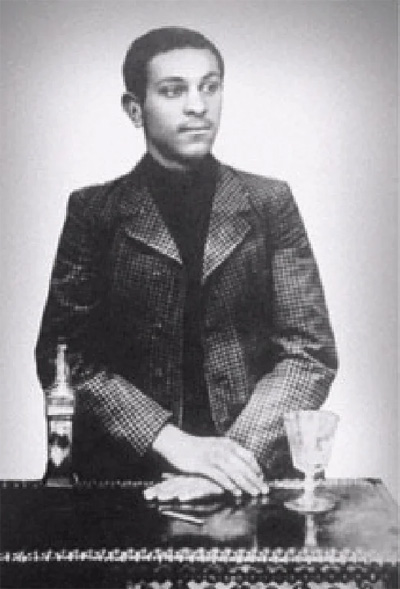

Following his passing, there were unfortunate circumstances regarding the dissipation of his considerable wealth and possessions by his heirs, particularly his eldest son Abdullah Mirza, who was his paternal half-uncle. This resulted in the personal desires of the heirs taking precedence over the preservation of Abbas-Ali Khan’s legacy.

Abbas-Ali Khan’s life and contributions shed light on a prominent historical figure who served in a significant administrative role and enjoyed close connections with the court of Nasser al-Din Shah Qajar. His religious devotion, charitable nature, and positive character traits left a lasting impact on those around him, despite the challenges faced in the preservation of his wealth and possessions after his passing.

Life of Abbasali

Names: Abbas-Ali Beig, Karbalaei Abbas-Ali, Kal Abbas-Ali, and Karbalaei Abbas-Ali Gomrokchi.

The precise birthdate of Abbas-Ali is not definitively known, but based on the research conducted, it can be estimated that he was born between 1851 and 1856. Abbas-Ali’s father, Haji Gholam-Ali, hailed from Shushtar and was renowned as one of the wealthy businessmen during the era of Naser-al Din Shah. Like other affluent individuals of the time, Haji Gholam-Ali likely supported the monarchy financially (some family elders identify Abbas-Ali’s father as Karim, although there are no available documents to substantiate this claim).

It is believed that Haji Gholam-Ali introduced his son Abbas-Ali to the courtiers of Naser-al Din Shah in an effort to secure a position for him at the court, and it is possible that bribes were involved in this endeavor. The talented and young Abbas-Ali later earned the title ‘Abbas-Ali Beig’ and was appointed as the head of the royal pantry and ceremonies of Naser-al Din Shah. During that period, the position of head of the royal pantry and ceremonies held significant importance in the Shah’s court, as head of the royal pantry and ceremoniess who could satisfy the Shah were often promoted to even more influential positions. Historical accounts indicate that Agha Ibrahim Amin al-Sultan, the grand vizier, served as Naser-al Din Shah’s court head of the royal pantry and ceremonies during his youth and, despite being barely literate, managed to ascend to the position of grand vizier through his intelligence and shrewdness.

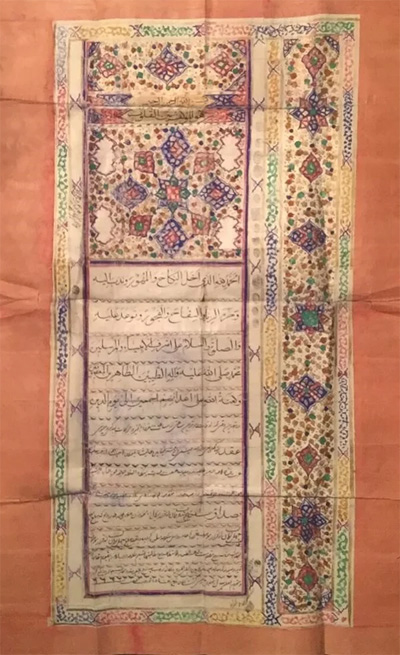

In 1876, Abbas-Ali Khan married a court lady named Zivar Khanom, and their marriage certificate refers to him as ‘Abbas-Ali Beig, the head of the royal pantry and ceremonies of his imperial majesty.’ This marriage certificate is currently in the possession of Karbalaei Abbas-Ali’s eldest great-granddaughter, Ms. Mahindokht Parstabar. They had a son named Abdullah Mirza. Following the premature death of Zivar Khanom around 1881, Abbas-Ali Beig married another court lady named Ghamar Taj Khanom. This union resulted in three sons: Gholam-Hossein Khan, Mirza Mohammad Khan, and Gholam-Ali Khan. Gholam-Hossein Khan passed away during childhood, and Mirza Mohammad Khan was married and relatively young when he died. More information about Abdullah Mirza and Gholam-Ali Khan will be provided in the next section.

In his book titled ‘The Old Tehran“, Mr. Jaffar Shahri mentioned that the lease agreement for the Customs, which granted control of the Customs to Abbas-Ali Beig, was signed in 1301 AH (1883) by him and Mirza Ali-Asghar Khan Atabak “Amin Sultan,”

‘The grand vizier. Mr. Mahdi Bamdad’s book titled ‘Biography of Iranian Politician’ contains the following quote: ‘In 1301 AH (1883), Karbalaei Abbas-Ali or Abbas-Ali Beig served as the director general of Tehran’s Customs and accumulated significant wealth in this role. Karbalaei Abbas-Ali’s bazaar was among his possessions, and he owned various other real estates. After his death, his heirs squandered his wealth on self-indulgent activities. His descendants adopted the surname Gomrokian.’

Based on the written evidence mentioned in this text and further research, it can be concluded that this transfer of authority took place in 1309 AH (1891), and the aforementioned contract remained valid until 1895-1896 (there is also a slight chance that he held this position for two terms).

In some texts, Karbalaei Abbas-Ali is mistakenly referred to as the Minister of Customs, but this position did not officially exist during Naser-al Din Shah’s reign. The grand vizier would sign Customs rental contracts with dignitaries and well-connected individuals who submitted the highest bids, and these contracts were valid for specific periods of time.

Interestingly, the first Minister of Customs in Persia (now Iran) was a Belgian national named Monsieur Naus, who arrived in Iran during the reign of Mozaffar-al Din Shah to modernize and reform the Customs. One year later, in 1898, following Monsieur Naus’ successful performance and a substantial increase in Customs revenue, he was appointed as the Minister of Customs.

Karbalaei Abbas-Ali, like many of his wealthy contemporaries, resided in the Sangelaj neighborhood of Tehran and invested the money he earned from his economic activities into various development and construction projects. Some of these projects included:

- Karbalaei Abbas-Ali Bazaar: Only the Saqakhaneh building of the bazaar remains today.

- Abbas-Ali Takyeh: A structure built by Abbas-Ali.

- Karbalaei Abbas-Ali Hammam: A public bathhouse established by Abbas-Ali.

- Houses and estates near Abdol-Azim Shrine: Abbas-Ali owned properties in the vicinity of this holy shrine, which was visited by dignitaries and courtiers of the time.

It is estimated that Karbalaei Abbas-Ali passed away in the 1910s, and after his death, his body was transported and buried in the city of Karbala.

Regarding his other economic activities, Kamran was unable to locate documented information apart from the fact that Abbas-Ali had control over the slaughterhouse of Tehran for a period.

In a quote from Ghahreman Mirza Ein al-Saltaneh’s memoirs, it is mentioned that Kamran Mirza, son of Naser-al Din Shah, was reluctant to relinquish control of the slaughterhouse and would use excuses like a leg ache to retain his hold over it. The slaughterhouse generated an annual revenue of 67,000 Tomans, and the high taxes imposed on it resulted in the suffering of the people. The grand vizier assigned the task of addressing this issue to Karbalaei Abbas-Ali, effectively removing this revenue source from Kamran Mirza’s control. The quote implies Kamran Mirza’s dissatisfaction and inability to maintain control, comparing his efforts to ‘milking a ram.’

Regarding Karbalaei Abbas-Ali’s sense of humor, it is said that he would occasionally play pranks on local street vendors. However, to alleviate their anger and resentment, he would then gift them Ashrafi coins, bringing joy to their hearts. It is believed that this was Abbas-Ali’s way of giving charity to the poor.

There is an account regarding this subject where Abbas-Ali Khan purposely disturbed the goods of a street vendor, leading the vendor to become angry and curse him. In response, Karbalaei took out a few Ashrafi coins from his pocket and gave them to the vendor. The vendor was filled with happiness afterward. (It should be noted that each Ashrafi coin contained 3/44 grams of gold and was valued at approximately 10,000 Dinars.)

Karbalaei Abbas-Ali had a brother named Karbalaei Mohammad-Jaffar, but little information is available about his character and activities. Apparently, he did not possess the same capabilities as his brother. In 1876, Karbalaei Mohammad-Jaffar married Marziyeh Sultan, the daughter of ‘Amanullah Mirza Mohammad-Bagher Tayyeb Qomi al-Asl,’ a prominent figure of the time. They had a son named Hossein. Hossein Agha later adopted the surname Noruzi or Nozari, got married, and had three daughters.

Documents Mentioning Karbalaei Abbas-Ali’s Estates

- Karbalaei Abbas-Ali Bazaar:

“Karbalaei Abbas-Ali Bazaar is one of the most famous bazaars; it begins on Alborz St. near Monirieh Square and ends on the former Shahpour Street. Karbalaei Abbas-Ali was the director general of Customs during Naser al-Din Shah’s reign.”

(“The History of Tehran” by Hossein Shahidi)

- Abbas-Ali Takyeh:

This takyeh was located on Sirus St. near the Emamzade Seyed Esmaeil Shrine. A brief history of Tehran’s takyehs and mourning sites under the Qajar dynasty

(Shargh Newspaper)

- Abbas-Ali's Estates Near Shah Abdol-Azim Shrine:

“… Mirza Abdulsammad (Karvansaradar), the tenant of Abbas-Ali Gomrokchi, resides in his estate located near the Shah Abdol-Azim shrine…”

(An article about Khatunabad’s history)

- Karbalaei Abbas-Ali's House Located Near Shahr-e-Rey:

“Today, in the company of Nazem al-Ataba and Mohammad Mirza Ali Mahalati, and aboard a court carriage, I traveled to Shah Abdol-Azim shrine… from there we went to Karbalaei Abbas-Ali’s house, which is a pleasant, but rather Caravanserai-like kind of place (probably due to its vastness and too much comings and goings). We consumed kebab and yogurt there and rested.”

(From Etemad al-Saltanhe’s diary, written in 1894)

- Karbalaei Abbas-Ali's House and Garden Located In Tehran:

The first school in Iran was named Roshdieh School and was founded by Haji-Mirza Hassan Roshdieh (the founder of modern schools in Iran) in this house:

“Roshdieh School was founded in Ramadan of 1315 (AH) (1896) in Karbalaei Abbas-Ali’s garden located near the former Shahpour Street under the supervision of Mirza Hassan Roshdieh. In 1901, it was transferred to the Vagoon estate belonging to the late Mirza Mohammad Sepahsalar.”

(From “The History of Tehran” by Hossein Shahidi)

- Karbalaei Abbas-Ali Hammam:

These discussions took place in this Hamman on Monday, Shawwal, 1324 (AH) (1905): ‘Today in Karbalaei Abbas-Ali Gomrokchi’s Hammam, two of Haji Sheikh Fazlollah’s underlings and Gholam-Ali Khan, the youngest son of Karbalaei Abbas-Ali who is the valet of the court minister, and some other guys were talking to each other. They said the court minister repeatedly says that while residing in Tabriz he owed 20,000 Tomans, but ever since he moved to Tehran, he has settled all his debts, and now they can see how much he owns. Afterward, Gholam-Ali Khan swore that he doesn’t even know how much is spent on the court minister’s stable; 100 Tomans are the daily expenditure of his stable that does not include the wages of the equerry, postilion, and stableman.’

(From the reports regarding the government officials’ corruptions during Mozaffar al-Din Shah’s reign. Hassan Saqhafi Azazi Library)